Two decades, and four programmatic generations, into New York’s Brownfield Clean Up Program (BCP), most participants should consider it successful.

New York State surely should appreciate help cleaning up its brownfields, as well as the multi-fold return its program offers New York taxpayers on their investment.

Real estate owners and developers (and their lenders and investors) should enjoy the budget-patching cash that flows from their clean up and redevelopment of a brownfield site.

And municipalities and their citizens should value the reclamation and beneficial reuse of contaminated land in their backyards.

But it’s not all ribbon-cuttings and new playgrounds, of course. After all, the BCP is difficult and expensive to access, takes years and several skilled professionals to navigate, and can be extraordinarily risky for unsuspecting or unprepared owners and developers, and their investors.

The BCP was launched in 2003, resulting in 502 clean ups through Generation Three of the program (2021). The budget coffers of early generations of the program were nearly emptied by downstate projects that were relatively light on brownfield clean up, but heavy on redevelopment cost. That led to fool-me-once program amendments that capped tax credits available for “tangible property” costs (the cost of redevelopment) at a multiplier of the cost of the site preparation (clean up). We discuss this tax credit math in Part 2 of this series.

Since then, changes to the BCP have largely targeted public policy priorities. The most recent amendment proposal would cause brownfield redevelopment tax credits (BTCs) to trigger the application of Davis Bacon prevailing wage rates, which some industry members fear will reduce or even eliminate the net value of the BTCs for their projects. We discuss that proposal, and other recent and proposed changes to the BCP, in Part 3 of this series.

The stated objective of the BCP “is to encourage private-sector cleanups of brownfields and to promote their redevelopment as a means to revitalize economically blighted communities. … The BCP is an alternative to greenfield development and is intended to remove some of the barriers to, and provide tax incentives for, the redevelopment of urban brownfields.”

To become eligible for admission to the BCP, a site must be a “brownfield site” which is “any real property where a contaminant is present at levels exceeding the soil cleanup objectives or other health-based or environmental standards, criteria or guidance adopted by DEC that are applicable based on the reasonably anticipated use of the property.” Such exceedances generally are established through public and other record examination, site inspection, and soil and water testing, generally conducted by an environmental engineer, or other “qualified environmental professional”.

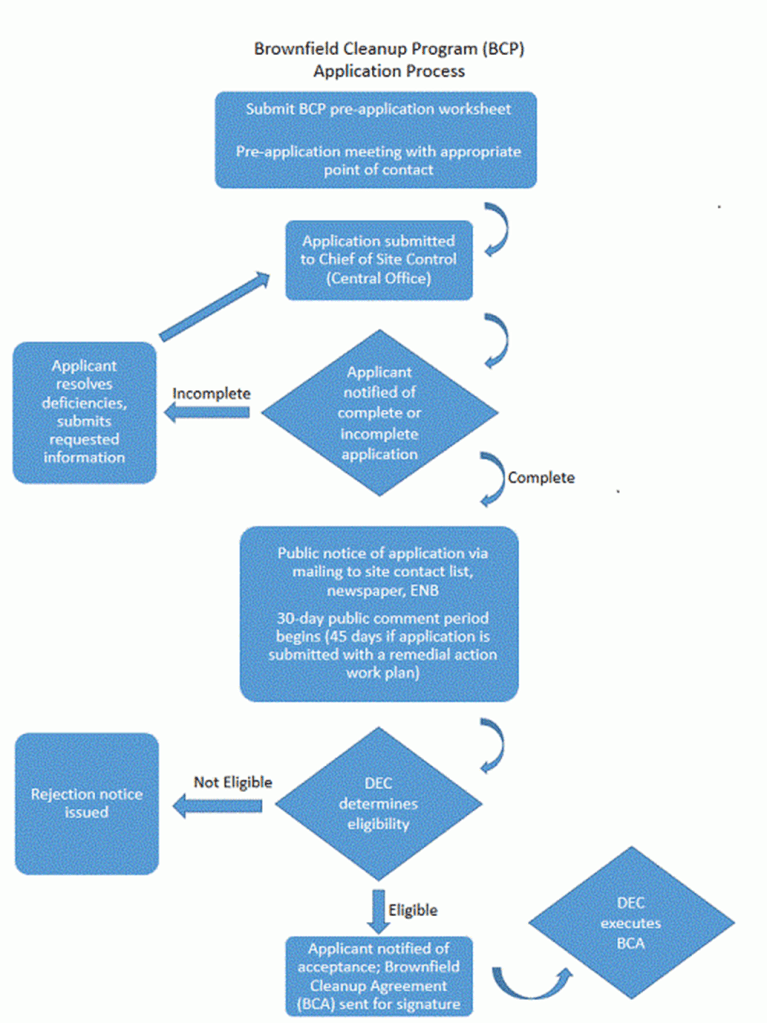

Owner-Developer-Applicants that believe their property may qualify for the BCP first must file a pre-application worksheet with the regional office of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). If regional DEC officials agree that a site is a valid candidate for the BCP, the Owner-Developer-Applicant then must file a full BCP application, generally with the assistance of a BCP consultant.

In the BCP application, the Owner-Developer-Applicant further establishes the scientific basis for its site’s eligibility, describes the level to which the site will be remediated (known as remedy selection), and details the future reuse of the site.

After a BCP application is deemed complete, a public notice and comment period commences, after which DEC determines whether a site is eligible. If it is deemed eligible, the Owner-Developer-Applicant and DEC sign a brownfield cleanup agreement. As of 2023, a $50,000 application fee is due at the time of final application, unless a hardship waiver is granted by DEC.

[Source: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation]

As mentioned, an Owner-Developer-Applicant must elect a “remedy” in its BCP application. Track 1 clean-ups result in no future restrictions on the property. This is the remedy elected for sites that are reused for new single-family homes, for example. Tracks 2, 3, and 4 are all “restricted”, that is they are site-specific approvals with reduced (from Track 1) clean up responsibilities and ongoing site management obligations. Track 1 provides the largest amount of site preparation tax credits, with the other tracks offering varying lower levels of tax credits, depending on level of clean up and the site’s location.

After the DEC approves a site’s remedial investigation work plan (testing plan), the Owner-Developer-Applicant then develops a remedial action work plan (a.k.a remedial work plan), which evaluates and recommends “remedial actions and applicable technology to address site contamination.”

Upon DEC’s approval of the remedial action work plan, an Owner-Developer-Applicant may commence its clean up knowing that its efforts likely will generate BTCs. Upon completion of the clean up, DEC issues a certificate of completion (COC). BTCs for site preparation are available for the year in which the COC is issued. For cleanups other than Track 1, DEC will require the execution and recordation of an environmental easement that notifies the public of the restricted nature of the clean up, and of any ongoing site management obligations.

Next time: Digging Deep: Cleaning Up New York’s Brownfields – Part 2, The Tax Credits

_________

Jason Yots has been a real estate and tax credit development attorney since 1996, and currently is a partner at the law firm of http://www.chwattys.com. Jason also is the founder of http://www.preservationstudios.com, an historic preservation consulting firm, and http://www.commonbondrealestate, an historic rehabilitation firm. He is based in Buffalo, NY.

Leave a comment